Takao-Shinjuku-1996 – Christopher Nailer

Shinjuku, Tokyo, October 1996

Whenever I’m in Shinjuku, part of me is always looking for Takao. Great big Ainu bear of a man. Hearty laugh, this irreverent, maverick, left-wing romantic cynic, my confessor and guide. When I was living here, even in this city of 15 million, I would sometimes run into him by chance. Now it seems I’ve lost him. In the middle of the afternoon I stroll down the alley that leads from the main road in front of the station – past the small traffic island where the glue-sniffers hang out and the great big electronic billboard flashes ‘Coke’ or ‘Fuji Film’ while you wait to cross – then down the hill towards the Bungeikan and the Kuyakusho – a narrow, winding alleyway paved in flagstones and lined with small trees, softening the jumble of bars, night-clubs, hang-outs, eating-places. This was his world. He introduced me to it, suggesting we meet here. The movie houses in that hidden quadrangle you always felt you weren’t going to find amongst the maze of buildings and signboards, but somehow always did. Here was the basement flamenco joint full of Japanese Espanophiles dressed up to the false eyelashes doing not-bad imitations of Latin Americans: jet-black hair, olive skin, almond eyes, gushy air-kissing, hailing each other as ‘Roberto’ and ‘Carlita’ loudly in Spanish; a female dancer rustling off in all her organza flounces, a queer male dropping his stamping, nostril-flaring macho and slipping back into effeminate the moment he steps off stage. Here it was Takao introduced me to a Japanese guitarist, just recently returned from Madrid, who taught me for a while. Not far from here was the famous sushi bar with huge sumo-wrestlers’ hand-prints in sumi-ink on rice-paper along the walls, personally signed and highly collectable. Also the small sakaya where we went one night. Drunken local workers insisted that the weirdo-Japanese-speaking foreigner sing along to their sentimental wartime army songs – ‘Kuroda-bushi’ and the tune that all the timed traffic lights play electronically as a ‘walk’ sign for blind pedestrians. Takao, moving effortlessly in this floating world of light and dark. Takao, the leftie, half amused, not singing along with their sentiments.

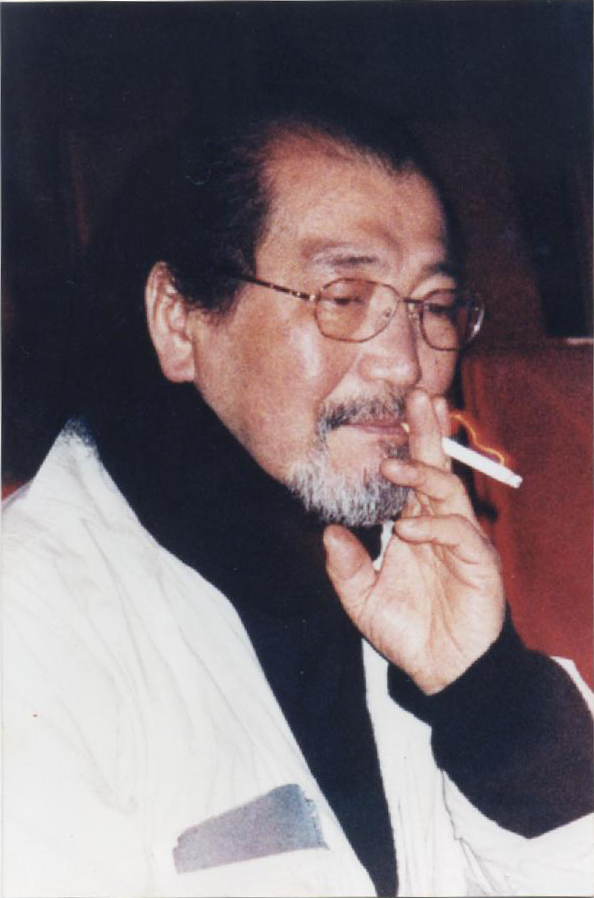

Somewhere I have a photo of him taken in half profile in another bar just before I left. Dark features, dark beard, looking away, sombre. The battered English workman’s cap that he wore everywhere, indoors and out. The dark waistcoat hanging open across his big chest. He didn’t much like photos. I have a scribbled address he gave me for his brother in Sao Paolo where he planned to emigrate one day. I wrote there once from Melbourne only to get my letter back. I have Claudia’s description of her relationship with him floating in my head: “We make good love together but he says I am too bourgeois because I like to have good equipment for my music.” It was Claudia who introduced me to him. Claudia, small, intense, electric. Claudia with the desaparacido activist husband, now lost completely beyond the reach of the Brazilian Colonels. Claudia, who I also might have loved if life had been simpler, if I had been braver… She became my sister. Claudia, now working with the earnest professor of early Japanese court music – his star clambering, one paper at a time, up the mountain of a sterile academic aesthetic – poor substitute for the hearty fish-grabbing bear-man, Takao, my Japanese brother.

Walking down this same alleyway with my girlfriend, Elaine, newly pregnant in 1975, both of us wondering ‘what next?’ Suddenly there he was, coming towards us with his ironic half-smile – “Omedetō – deshō…” “Congratulations..?” He’d heard the news from one of his girlfriends who he’d introduced to swap English for Japanese conversation with Elaine. Kiyoko arrived at the flat one evening, Elaine throwing up in the toilet, and she worked it out. Takao’s handshake matched my mood with just the right degree of doubt. He was the non-scholarly part of me, my relief from a life devoted to, paid for by, scholarship. He was my dramatic, theatrical counterpoint. In different moods he was in love with, or out of love with NHK, where he worked on studio lighting. In love with, and out of love with dance and dancers, fighting the Japanese convention of lifetime employment. He’d work, save up, get an idea, resign, and spend all his savings rehearsing a new show. Then broke again, he’d get his lighting job back at the TV studios once more. One time he got a labouring job at Tsukiji, unloading fish from the fishing-boats at first light; maybe to avoid having to compromise with the mass media world again; or maybe he’d resigned once too often…

The Tokyo Goethe Institut hosted one of his shows – a formless experimental modern piece with dancers, chairs, streamers – for one night only. It was well-attended, had some high points, but it went on too long. In the fresh-scented springtime outdoor garden people drifted back to the drinks under the striped marquee. At one point, one of the dancers tied us to our chairs with streamer tape. Interesting. But no-one came and untied us. I sat there, half in, half out of the performance as it fizzled to an end. My theatre training protested: “You set up a convention like that and then don’t follow it up. You break the barrier between performer and audience, tie us into the world you’ve created but then you’re not consistent with it, even as we’re trying to come with you…” He smiled; “You think too much about rules.”

Another time we went together to a theatre near Asakusa to watch someone else’s rehearsals… He suggested it; I was free that day, so I went along. A jazz ballet thing being put together by another one of his girlfriends. It was rhythmic, athletic, sometimes stark and jarring. “I don’t like jazz dance,” he said quietly as we sat up in the high seats at the back, “It’s superficial.” But he gave his time generously for the girl who was creating it. After watching a whole day’s rehearsals he made encouraging comments. We all went and ate together in a nearby restaurant. The dancers were happy, bubbly, tired. I was relaxed, eight pretty women and my unimpressible Japanese brother, chatter flowing effortlessly. I can remember a voice in my head said, “Hey, you’re speaking this language without thinking..!” A foreigner – you never get over that – but no barriers any more. Within a couple of months I’d left Japan for ever. It was Ushi-no-hi (ox day), late July, the evening air still warm, the restaurant packed and noisy. We took up a table of 10, all crammed close together, eating roast eel, jammed in alongside other customers – Unagi (eel) a tradition on this day – something to do with symbolic euphony of the ‘U’ sounds in both words – I never discovered any closer connection than that. Roast eel on a bed of steamed rice, rich juices flowing into the bentō – sumptuous. Back in my study I was struggling to write a seminar paper on Australian Aboriginal rock painting – a subject about which I knew absolutely nothing but which a group of fellow research students had asked me to talk about, and so, as the token Australian, I was having a go… All the commentaries spoke about the connection between dreamtime paintings and ceremonies. And suddenly dance seemed to be the link: creation, story, ceremonial performance, stamped footprints, animal tracks, painted image, identity with landscape, proto-script … We drank, the night deepened, I blathered on. The girls flirty, flattered me like I was Einstein. We all went home delighted with our performances. That day I might have stayed for ever.

Then in my last few weeks, while part of me was already beginning to pack up and disengage, Takao brought me a project – to translate a mime script of Gunter Grass’ – ‘Der Arzt’ (The Doctor) – into Japanese so that he could work it up into a performance. I knew almost no German, but, no matter, I was living by then back at the student hostel with no shortage of Swiss, Hungarians, Czechs, Poles, Bulgarians… I worked through it with a French-Swiss fellow – Jean-Michel – who knew enough German. He sat on the floor of his room with his Japanese girlfriend in his lap, explaining the text to me in his halting Swiss English, Deep Purple’s ‘Burn’ album blaring on the stereo. I put it into Japanese, which his girlfriend corrected. Then young Mr Kondo, one of the Ministry of Education clerks who helped to run the hostel, who’d just graduated in German Literature, reviewed the whole thing and made corrections. It was a surrealist piece about a doctor-patient relationship. A young woman patient pretends to be pregnant by the doctor – entrapment, psychological twists within byzantine intrigues – I forget the detail now but it explored the theme from many angles. Perhaps he meant it as a message. In my naïve studious way, I closely rendered the language and missed the message. Did he ever perform it? I wonder. We had resolved – in that way good friends do when they part for what will probably be forever, who seek to create even fictitious links that might endure a while beyond the moment of parting – that we would arrange a synchronised performance of the piece, separated geographically – Takao in Tokyo and me in Melbourne – a kind of hemisphere-shifted bilingual parallel-event-happening. I guess, in a way, I did indeed perform this, without knowing it, for several years after our daughter was born, before Elaine left for the first time, before family life became strange, stretched thin, before I stopped writing to people I cared about.

The dark photo of Takao in half-profile, the address written in Takao’s big handwriting on a scrap of paper torn from a notebook – these time frozen fragments – I held onto them down the years. Several times I sent them off with friends who visited Japan in the intervening decades saying, “If you’re in Shinjuku, you must try and track down this fellow for me…” All the urgency of a pilgrim hoping for a relic back from the holy land. They never quite understood. Each time they’d come back and return my fragments, saying, “Wow! Had a great time in Tokyo! What a wild place! Didn’t have time to track down your friend though, sorry.” Friend? Friend? The other half of my soul, more like. Takao is Shinjuku! How can you visit Shinjuku without finding Takao? And now, more recently, I’ve been coming on the pilgrimage myself, thanks to this company or that company hiring me, each time stealing an afternoon after the business meetings to wander down these alleyways again. And each year, the haunting of this place gets worse. Last time I called his old phone number and the woman who answered had never heard of him. This year, my daughter turns 20 and I can’t find her Japanese godfather. I wouldn’t know where to start. This time Shinjuku is unbearable. I’ve completely lost him. I keep my pilgrimage short, almost clinical. I walk the places that are still recognizable with a keyed-up ache in my guts, refreshing old memories of rat-runs I could once do blindfolded. Stop somewhere for a coffee behind a window-pane, just to pause and watch the flow of the crowd passing, just in case that big figure walks past again. Crazy hope, memory, regret, senseless anticipation, all pointless. I walk back uphill to the station entrance breathing heavily with loss and relief. Something says, “Takao’s gone from here.” Maybe he emigrated after all. Everything’s different. Only the glue-sniffers never change.

Christopher Nailer

Senior Lecturer at the Australian National University, Canberra, Australia